Snot Science: A snotty setup

Here’s how to test how far a sneeze will spew snot

Proper hygiene means covering your nose when you sneeze. But a lot of people don’t. How far away do you have to be to stay safe from their germs?

Wavebreakmedia/istockphoto

This article is one of a series of Experiments meant to teach students about how science is done, from generating a hypothesis to designing an experiment to analyzing the results with statistics. You can repeat the steps here and compare your results — or use this as inspiration to design your own experiment.

It’s flu and cold season, when everyone is trying hard not to get sick. A flu shot may help you to avoid the worst. But no matter how much you try to protect yourself, it seems someone nearby is sneezing away through most of the winter. Those sneezes spray out tiny drops of mucus, in which cold and influenza viruses hide. Sometimes it’s a fine spray, and other times, the snot gets everywhere. It’s pretty disgusting. But it’s also a good opportunity to ask some questions: How far does each kind of snot travel? And how far away do you have to stand to stay safe from viral spread?

I try to answer these questions in our first DIY Science video. And here, I will show you how to do this experiment yourself, how to analyze the data and how you can interpret the results.

The idea for this experiment came originally from an experiment on Science Friday. The website showed how to plot out sneezes using a histogram — a graph showing how data points are distributed over a range. I decided to turn this into a different experiment — one that compares thick snot to thin.

The two types of mucus differ in their viscosity — a measure of a fluid’s resistance to flow. Thick gloppy boogers have a high viscosity. They slowly ooze out of your nose. Thin, drippy snot has a low viscosity. It drips quickly.

We can use what we know about viscosity to form a hypothesis — a statement that can be tested. The statement will compare a control (something in the test that will not change) to a variable (some factor that is changing).

Hypothesis: Thin snot will fly farther and spread more than thick snot

Now we have a hypothesis. How do we test it? In the Science Friday experiment, a small plastic dropper served as a fake “nose” to spray colored water onto paper. This serves as a sneeze model — a representation of something that happens in the real world.

I decided to do something similar, using a dropper with colored ”snot.” Because the best experiments are repeated many, many times, I didn’t want to replace the paper over and over. Instead, I used plastic shower curtains, which I could wipe off in between “sneezes.” (At the bottom of this post, I’ve written down my materials list, along with the cost that I paid for each item.)

Creating snot plots

For the experiment, I wanted plenty of open space. To film the video, my team used a large conference room. I lined up white shower curtains and taped them to the floor. At one end of the shower curtains, I set up a table with my artificial nose on it. Then, using a permanent marker and a measuring tape, I drew a five-meter (16.4-foot) line on the tarp stretching out from the table. I marked the line every half meter (50 centimeters, or about 20 inches).

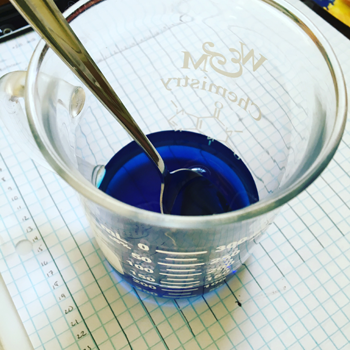

Then I made my “snot.” For thin snot, I used half a cup of water (about 118 grams) and a few drops of blue food dye, enough to turn it a nice dark blue. (I didn’t use red or yellow in this test. Yellow wouldn’t show up well on the tarp, and red looked a little too much like someone was sneezing with a bloody nose.)

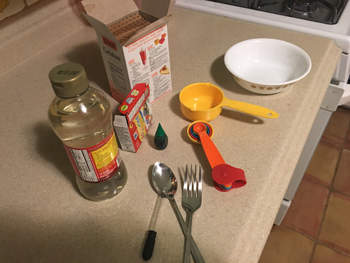

To simulate viscous mucus, I couldn’t use water alone. I needed to find a combination of substances that would more closely stand in for snot. Mucus is mostly water, but added sugars and proteins give it its glop. So I needed fake snot with the same or similar ingredients. I realized I could use gelatin for my proteins and corn syrup as my sugar. With water, they make a good substitute for thick, gloopy snot.

I followed the recipe I found here, but I discovered that making snot is harder than it might seem. I had to tweak the recipe. To get consistent results, follow these directions carefully:

- Bring a half cup of water (about 118 grams) to a boil in a small pot.

- Take the water off the heat immediately. The original recipe says to keep the water boiling, but I found that if I did that, my goo never thickened.

- Mix three tablespoons (45 grams) of gelatin into the hot water and add food coloring (I used green). The gelatin tends to clump; stir with a fork to break up the clumps.

- Add a quarter cup (59 grams) of corn syrup. When you dip your fork in again, it will bring up long, gloppy strands of snot. Do not stir the corn syrup in vigorously as this will also stop the mucus from forming. To stir, stick in your fork and make a very slow, lazy circle or two. No more than that.

The mixture will thicken more as it cools. To keep it at the same thickness, add one tablespoon of water (15 grams) to the mixture every five minutes. Remember to stir as little as possible.

You can — if you want — eat this mixture. I wouldn’t recommend it. It smells.

In experiments, it’s important to keep everything you do as consistent as possible. The most important variable for me was thick mucus versus thin mucus. What if temperature affected the thickness of my liquid? My mucus was hot. But the water I was using was not — it had just come from the tap. I made sure that both of my snot mixtures were the same temperature. Because the recipe for the thick snot requires bringing the water to a boil, I brought my thin snot to a boil, too.

Once I had my thick and thin mucus, I loaded each into a dropper, smacked the bulb (you can yell ACHOO! for good measure, if you want) and measured how far the snot squirted. For each “sneeze,” I measured how far the fluid managed to fly. I also looked at where the most fluid was concentrated by counting the number of droplets present for each half meter of tarp.

Sneezes vary a lot between people. And drops squirted from a dropper vary, too. So I couldn’t squirt each type of snot once. I needed to squirt each kind many times.

Running the experiment multiple times would help me to avoid two types of error. I would make a Type I error if I concluded the two kinds of mucus were different when really they weren’t. This is a false positive. I’d make a Type II error if I concluded the two kinds of mucus were the same when in fact they were different. This is a false negative. I can never totally eliminate the possibility of these errors, but running the experiment more than once lessens the likelihood that I make them.

But how many runs of my experiment would I need? To find out, I would have to do some figuring. Scientists generally agree that a five percent chance of a false positive (or 0.05) is acceptable. This is called an “alpha.” False negatives aren’t quite so bad, and an acceptable risk is 20 percent or 0.2, and called “beta.” A beta of 0.2 would give me a power of 0.8, or an 80 percent probability of finding a difference between my two kinds of snot. With a power of 0.8, I could use a chart from a 1992 paper by Jacob Cohen of New York University (a free copy is here; look at table 2). This chart tells me that to compare two groups (finding the “mean difference”) with an alpha of 0.05, I would need to squirt each type of snot 26 times to detect if there is a large difference between them. (For more about power analyses, see this post here.)

So I did. I squirted, measured and carefully wiped up each type of mucus 26 times. I made sure to write down all my measurements as I went along.

What did I find? In my next post, I’ll show you my data and how I grouped together and compared all of my snot spatters. If you’re trying this yourself, please leave notes in our YouTube video comments, or send me a tweet @eureka_labs! Did you have difficulty with the thick snot recipe? Did you find a better one? Let me know!

SSP/Explainr

Materials List

- Plain white shower curtains (two, $3.99 each)

- Permanent marker (pack of three, $5.67)

- Scotch tape ($1.99)

- Food coloring ($3.66)

- Sponge (for cleaning the shower curtains, pack of three, $2.96)

- Plastic transfer pipettes (pack of 100, $6.99)

- Small hot plate (Oster single burner, $24.97)

- Small pan (one quart, $12.43)

- Measuring cups ($7.46)

- Measuring spoons ($5.36)

- Gelatin (Knox brand, $2.99)

- Corn syrup (Karo brand, $2.56)

Follow Eureka! Lab on Twitter